Learning from Success: Centering Community in Infrastructure Development

Learning from Success: Centering Community in Infrastructure Development

These U.S. Communities Challenged the Infrastructure Development Status Quo with Their Innovative Projects. Here’s What We Can Learn from Them.

This is the second part in our series exploring the opportunities presented by recent historic investments in United States infrastructure and the potential to transform the status quo. You can read the first blog on a new approach to centering community in infrastructure development here.

Historically, infrastructure development in the United States has functioned on a status-quo approach, prioritizing a one-size-fits-all “solution” over collaboration with communities to build the infrastructure they want and need. A top-down approach rarely involves meaningful community involvement, consultation and ownership, which are key to attaining beneficial and sustainable outcomes. This is particularly true for communities of color, which primarily have been impacted by damaging and divisive infrastructure investments, such as the policies enacted by the 1956 Federal Highway Act.

More recent investments in infrastructure at the federal level have helped to create an inflection point in the U.S. We have the opportunity before us to truly shift the status quo by centering meaningful community engagement, vision and ownership. Many coalitions, like the Community Connectors grant program, across the country already are working on this very shift.

In the first part of this series, we outlined ways that changes in implementation could alter the future of mobility, justice, health and climate outcomes. We focused on four approaches:

- Transportation Decarbonization Using Equitable Solutions

- A Focus on Justice

- Embedding Community-Led Solutions, Values and Wisdom

- Shovel-Worthy > Shovel-Ready Projects

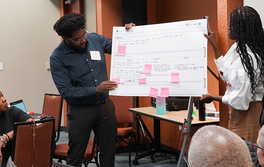

Now we are showcasing projects that center community voices, knowledge, culture and aspirations to build power in their respective communities.

The following examples show how communities have been involved and exercised their agency over development decisions through examples of successful, community-led, shovel-worthy infrastructure projects. These projects, which were completed prior to the recent influx of funding, embedded the above four tenets in their approaches. In the next part of this series, we will highlight federal and philanthropic programs that exemplify approaches that center communities.

A Community Plan to Improve Health Outcomes in Eatonville, Florida

To address health issues in Eatonville, Florida, the town’s Community Redevelopment Agency implemented holistic programming, which included safe streets and sidewalks, increased access to care and community engagement, a weekly vegetable delivery service and additional housing and education.

Founded in 1887, just after the Civil War, and located just outside of Orlando, Eatonville is the oldest historically Black-incorporated town in America. From the 1950s–60s, Interstate 4 (I-4) cut through the community and provided no interchange for residents to access the highway. Today, the citizens of Eatonville are combating high levels of poverty, unemployment, lack of access to quality food and health challenges, such as occurrence of diabetes at three times the national average. Despite the challenges they face, residents see the community as thriving, as one resident told the town council at a vote to (dis)allow a developer to buy the last 100 undeveloped acres in Eatonville.

Eatonville has a long history of strong civic engagement. In 1987, when a planned project to widen I-4 would have expanded further into the center of town, N.Y. Nathiri, a librarian and college writing teacher, founded the Association to Preserve the Eatonville Community, Inc. (PEC). PEC fought back against the highway widening project and now elevates Eatonville’s heritage and historical and cultural resources to revitalize the community and promote economic development. As part of a deep cultural history, residents often cite Eatonville as the birthplace of Zora Neale Hurston, an author and anthropologist who wrote about racial struggles in Florida and the American South.

In 2018, Eatonville won the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Culture of Health Prize, which allowed the town to continue its work. In the run-up to receiving the prize, the Polis Institute worked with residents through an in-depth community engagement process that included charrettes, training community ambassadors and leaders, community development workshops, community asset mapping and a community survey. Notably, the community engagement process was in addition to the Eatonville community’s determination for self-advocacy and dedication to preserving its cultural and historical assets in the face of external development pressures that did not meet their needs.

Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation

"The people of Oceti Sakowin Oyate are undergoing a revolution." — Amy Jakober

The Lakota, Dakota and Nakota peoples (known together as Oglala Lakota) of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation are working to create models of change for a brighter future and heal the past harms of colonialism. In the southwestern part of what is modernly known as South Dakota, the Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation (Thunder Valley CDC) is implementing Regenerative Community Development, part of which creates “an ecosystem of opportunity as a point for leveraging regional equity” to overcome intergenerational poverty, high suicide rates and poor health outcomes.

Working with the First Nations Development Institute, Thunder Valley CDC provided a series of grants through the Native Youth and Culture Fund to develop a community plan. Through Thunder Valley CDC’s growth, they have initiated several programs including a Workforce Development Through Sustainable Construction Program, Food Sovereignty Initiative, Lakota Language Initiative and Sustainable Home Ownership Program. This work centers justice and shovel-worthy projects to meet the community’s vision for what a thriving community that centers the Oglala Lakota way of life looks like.

Critically, Thunder Valley CDC’s approach focuses on a community plan. This approach recognizes that a community’s ability to thrive goes much deeper than a singular project designed to solve a single issue. Instead, Thunder Valley CDC centers a holistic approach to community-defined development that notes the interconnections among youth engagement, food security, workforce development and home ownership, as the Oglala Lakota have.

A Community-First Village in Austin, Texas

Mobile Loaves & Fishes, a social outreach ministry for people experiencing housing insecurity in Austin, Texas, is leading an unprecedented collaborative effort to mitigate homelessness in the city.

The Community First! Village provides affordable, permanent housing and opportunities to fundamentally care for and serve those coming out of chronic homelessness. The 51-acre village is currently home to 350 formerly unhoused residents. The village master plan intentionally encourages community building through outdoor communal kitchens and green spaces, including an organic farm. There are also micro-enterprise opportunities for residents to earn an income. Facilities to support this work include an auto shop, an art house, pottery facilities, a blacksmithing shop and a woodshop. The village has also installed a bus stop and has walking and biking paths throughout.

The Community First! Village is a very literal example of a community plan that is centering community building and harm repair. Focusing on justice and investing in shovel-worthy, rather than shovel-ready, projects often involves taking a multi-issue approach, as well as focusing on a community’s art and culture, access to healthy food, housing, jobs and sustainable transportation options.

These projects exemplify community building and harm repair from within the communities themselves. Each of these unique, place-based approaches was developed for distinctly different reasons, yet all show examples of the types of shovel-worthy investments this moment is calling for: those that are community-led, -needed and -inspired. These projects also go beyond the single-project approach by choosing to focus on holistic, equitable development by centering justice and a suite of community needs that are place-based and embedded within a community’s history and culture.

With the unprecedented funds currently available for infrastructure projects, governments and agencies implementing development run the risk of deepening inequalities, de-centering communities and maintaining the current status quo. However, this funding also represents an immense opportunity to center community vision early and often throughout the planning and construction processes, as well as a chance to embed single projects within larger community visions.

In the final part of this series, we will dive into current programs that are seeking to put communities first in infrastructure development — and how they are doing it.

This post was authored by Justyn Huckleberry, research and projects analyst for NUMO.

Header image: New York Department of Transportation/Flickr